The Ancient 360-Day Year

Many Christians think that the tropical year once consisted of twelve 30-day months, or 360 days. The original creation was “VERY GOOD” in Genesis 1:31. That means the sun and moon were in synchronization. How then did we end up with an awkward solar year (365.242 days) so out of step with a lunar year (354 days)? Why don't they synchronize? Why is the lunar month 29.531 days from new moon to new moon? The Bible clearly speaks of a 360-day year and a 30-day month. Why? Did the earth have a 360-day year with a 30-day lunar month within the last 6,000 years? Will it be that way in the future?

Immanuel Velikovsky's "Worlds in Collision", chapter 8, pp.333-345 goes through many of the records of ancient nations and proves that they all possessed a 30-day month and a 360-day year. Because of its length, we have kept it as a footnote at the end of this article.

Don't Change the Distance Between Sun and Moon

Before we alter the orbit of the moon, we should be aware that our sun and moon are the SAME APPARENT SIZE in the heavens, each about 1/2 degree, and that these apparent sizes vary from 31.5' to 32.5' for the sun, and from 29.3' to 33.5' for the moon giving solar eclipses in a series of gradations from annular through total, with a maximum totality of 7 1/2 minutes. Only on earth of all planets does such a situation exist, and only on earth are there intelligent beings who can appreciate and utilize this information obtainable in no other way. Through eclipses man is given a brief glimpse at the various atmospheric layers of the nuclear reactor which heats the earth. This PRECISION is proof of the existence of a Creator God. Any change in distance of either the sun or moon would significantly alter the height of ocean tides, which would in turn alter the period of regression of the moon's nodes, which would markedly alter eclipse cycles dependent upon the nodical month. The 19-year Metonic cycle would also cease to exist. Further, the 365-day calendar is also tied to the heavens, eight such calendar years of 2920 days being equal almost exactly to 5 synodic periods of Venus (584-day) equalling 2920 days. (see Kenneth Herrmann's Historical Record of a 360-Day Tropical Year). Venus draws a pentagram around the earth every eight years. Therefore the 365-day year is not so awkward after all. Yet even here, the 360-day year is 98.5% of the same accuracy.

Sundial Ten Degrees Backward

Why did early civilizations around the world use calendars with months of 30 days and years of 360 days? These calendars seemed to function well until 701 BC when suddenly it became necessary to change them. Most civilizations around the world began to modify their calendars to allow for 5 extra days for the year and 6 fewer days for a lunar year. A lunar year is 12 full months; a modern lunar year is 354 days (12 months x 29.5 days). Were these early civilizations incapable of accurately measuring the astronomical cycles that governed their calendars prior to the 8th century?

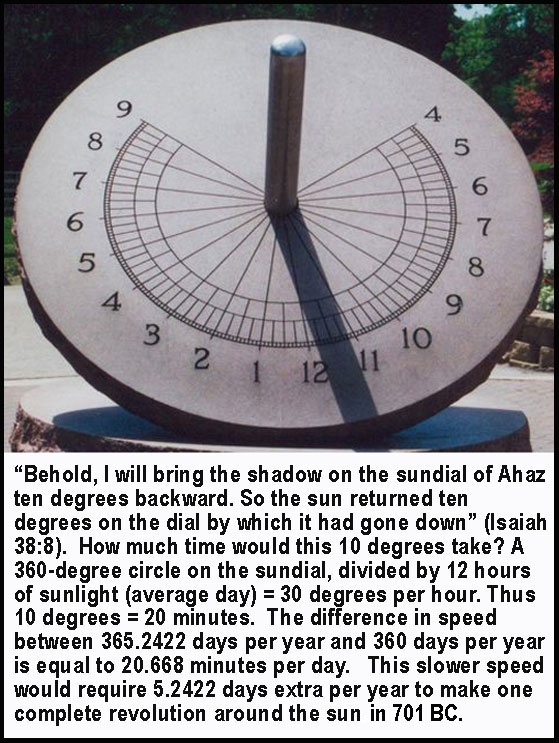

Let's look in the Bible at that time in 701 B.C. to see if we can find any changes mentioned. In Isaiah we discover the story of the sundial going backwards. Isaiah 38 mentions Hezekiah, the king of Judah, a man near death. Isaiah delivered God's message that he would die. Hezekiah prayed to God and God told Isaiah that He heard Hezekiah's prayer and would add 15 years to his life. God even gave Hezekiah a sign that He would do this. "Behold, I will bring the shadow on the sundial of Ahaz ten degrees backward." So the sun returned ten degrees on the dial by which it had gone down. (Isaiah 38:8). This story is repeated in 2 Kings 20:1-11.

Accelerating Earth's Orbital Speed

How much time would this 10 degrees take? A 360-degree circle on the sundial, divided by 12 hours of sunlight (average day) = 30 degrees per hour. Therefore 10 degrees = 20 minutes. The earth is orbiting the sun at 18.51 miles/second and has been doing so for thousands of years. This speed of 18.51 miles/second means that to make one orbit of the sun (one complete circle) will take 365.2422 days. If the orbit of the earth is speeded up to 18.78 miles/second we would end up with a year that is 360 days long. If we had a year of 360 days and slowed the orbit of the earth from 18.78 back to 18.51 miles/second then the year would equal our current solar year of 365.2422 days per year. The difference in speed between 365.2422 days per year and 360 days per year is equal to 20.668 minutes per day. This would not affect our 24-hour time period (rotation of earth) but it would take the earth 20.668 minutes less time per day to travel that same distance in its orbit around the sun. In other words, 20.668 minutes/day x 365.2422 days = 7548.768 minutes total which is the same as 125.8128 hours or 5.2422 days. Thus 365.2422 days -20.668 minutes per day = 360 days.

If you had a year that consisted of 360 days and slowed the orbit of the earth around the sun by .27 miles/second (The difference between 18.78 and 18.51 miles/second), you would end up with a year that takes 365.2422 days. This slower speed would cause 5.2422 days extra per year to make one complete revolution around the sun. We have only slowed the speed of the earth down. We have not changed spin of the earth in a 24-hour period and we have not changed the speed of the moon around the earth.

The Moon Takes Care of Itself

However, if the earth had a year of 360 days (meaning earth's orbital speed is 18.78 miles/second), the moon would now automatically have a 30 day lunar month without changing the speed of the orbit of the moon! This is because the moon takes about 27.3 days to make one complete orbit around the earth with relation to the stars. But the earth is also moving around the sun pulling the moon with it. The earth orbits around the sun once every 365.2422 days (meaning earth's orbital speed is 18.51 miles/second). The earth and moon in 27.3 days have moved as a system about 1/12 of the ways around the sun. This means that from one full moon to the next full moon, the moon must travel 2.2 extra days before it appears full. This is due to the curve of the earth's orbit around the sun. The moon is nonetheless making one complete orbit (circle) in 27.3 days, but to line up with the earth and sun to become a full moon again it takes 29.531 days.

Therefore, 29.531-day lunar months x 12 lunar months = 354.372 days per lunar year. This is a difference of 10.87 days a year between a lunar year and a solar year of 365.2422 days per year. If we did not speed up the orbit of the earth but had our current speed of 18.51 miles/second and let the earth travel half a day further, then at 30 days we see that the moon has gone half a day past the full moon -- no longer in alignment. (To achieve a full moon the moon must be in a straight line with the middle of the earth and the sun.)

Now if nothing else is changed except to increase the speed of the earth's orbit to 18.78 miles/second to achieve a 360 day year, then the time it takes from one full moon to the next full moon would be 30 days. The moon would still be making one complete orbit every 27.3 days but the moon would now need to travel 2.7 extra days (added to the 27.3 days) to become full again and in perfect alignment. Thus 30-day months x 12 months = 360 days per lunar year.

By adjusting the speed of the earth around the sun to give us a year of 360 days we automatically end up with a month that equals 30 days. It just so happens that all ancient calendars had twelve 30-day months, which equaled 360 days. These ancient calendars also had one solar year which equalled 360 days. All these 360-day solar/lunar year calendars suddenly began to change in the 8th century BC to either a 365-day solar year or a lunar year of 354 days per year -- or both. This is when the Bible tells us the sun moved backward on a sundial ten degrees, which equal about 20 minutes. The difference between 360-day year with a 30-day month and our 365.2422-day year with a 29.531-day month is orbital speed, which can also be translated into time, about 20 minutes extra per day.

Summary

At the creation of our perfect world -- and showcased during the time of the flood -- the year was 360 days long with 30-day months (Genesis 7:11,24 and 8:3-4). This is how 150 days, counted from the seventeenth day of the second month, and ended on the seventeenth day of the seventh month (Genesis 7:11,24 and 8:3-4) equal exactly five months of 30 days each. Then the year became our modern 365.2422 days per year in 701 BC as reflected in the calendar changes around the world at this time. The story in Isaiah 38 tells us about God adding years to Hezekiah's life and using a miracle to prove it. That miracle implies accelerating the earth's orbit so that a 360 day year with a 30 day month becomes our modern 365.2422 day year with a lunar month equal to 29.531 days. The earth may be headed for a 360-day year again! Daniel 7:25 speaks about the last part of the tribulation with the Antichrist in power as lasting three-and-one-half years. The book of Revelation 11:2 and 13:5 describes the same period of time as being 42 months. Revelation 11:3 and 12:6 tells us that it is 1,260 days. Therefore 1,260 days divided by 42 months = 30 days per month and 42 months of 30 days per month = 3 1/2 years exactly of 360 days per year. To achieve a 30 day month the earth's orbit around the sun must be speeded up so a year would = 360 days. "And unless those days were shortened, no flesh would be saved; but for the elects (chosen ones) sake those days will be shortened." (Matthew 24:22) "But as the days of Noah were, so also will the coming of the Son of Man be." (Matthew 24:37). Our Calendar of 365.2422 days per year x 3.5 years = 1278.3477 days. Revelation's Calendar of 360 days per year x 3.5 years = 1260. This time period of 3.5 years would be shortened by 18.3477 days.

According to the Bible (Gen. 5:23-24; Heb. 11:5) Enoch did not die, but was taken or raptured by God when he was in his 365th year. We believe this is a type of the rapture that will occur of those who "walk with God" in the end-time during a 365-day age. In other words, just before a destruction of the world, "as in the days of Noah", there was and is a 365-day age of both Enoch and modern man. After the rapture, we then revert to Noah's perfect 360-day age which is also mentioned in the book of Revelation.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Immanuel Velikovsky's "Worlds in Collision", chapter 8, pp.333-345 is summarized below:

We start in India. The texts of the Veda period know a year of only 360 days. "All Veda texts speak uniformly and exclusively of a year of 360 days. Passages in which this length of the year is directly stated are found in all the Brahmanas." (Thibaut, "Astronomic, Astrologie and Mathematik," Grundriss der indo-arischen Philologie and Alterthumskunde (1899), III, 7.) "It is striking that the Vedas nowhere mention an intercalary period, and while repeatedly stating that the year consists of 360 days, nowhere refer to the five or six days that actually are a part of the solar year." (ibid.) This Hindu year of 360 days is divided into twelve months of thirty days each. (ibid.) The texts describe the moon as crescent for fifteen days and waning for another fifteen days; they also say that the sun moved for six months or 180 days to the north and for the same number of days to the south. Here is a passage from the Aryabhatiya, an old Indian work on mathematics and astronomy: "A year consists of twelve months. A month consists of 30 days. A day consists of 60 nadis, nadi consists of 60 vinadikas." (The Aryabhatiya of Aryabhata, an ancient Indian work on mathematics and astronomy ~[transl. W. E. Clark, 1930], Chap. 3, "Kalakriya or the Reckoning of Time," p.51.) From approximately the seventh pre-Christian century on, the year of the Hindus became 3651/4 days long.

The ancient Persian year was composed of 360 days or twelve months of thirty days each. In the seventh century five Gatha days were added to the calendar. ("The Book of Denkart," in H. S. Nyberg, Texte zum mazdayasnischen Kalender (Uppsala, 1934), p. 9.) In the Bundahis, a sacred book of the Persians, the 180 successive appearances of the sun from the winter solstice to the summer solstice and from the summer solstice to the next winter" solstice are described in these words: "There are a hundred and eighty apertures [rogin] in the east, and a hundred and eighty in the west ... and the sun, every day, comes in through an aperture, and goes out through an aperture... . It comes back to Varak, in three hundred and sixty days and five Gatha days." ("Twelve months . . . of thirty days each ... and the five Gatha-days at the end of the year." (Bundahis [transl. West] , chpt. 5) Gatha days are "five supplementary days added to the last of the twelve months of thirty days each, to complete the year; for these days no additional apertures are provided .... This arrangement seems to indicate that the idea of the apertures is older than the rectification of the calendar

which added the five Gatha days to an original year of 360 days." (Note by West on p. 24 of his translation of the Bundahis).

The old Babylonian year was composed of 360 days. (A. Jeremias, Das Alter der babylonischen Astronomy (2nd ed., 1909), pp. 58 ff.) The astronomical tablets from the period antedating the NeoBabylonian Empire compute the year at so many days, without mention of additional days. That the ancient Babylonian year had only 360 days was known before the cuneiform script was deciphered : Ctesias wrote that the walls of Babylon were 360 furlongs in compass, "as many as there had been days in the ear." (The Fragments of the Persika of Ktesias (Ctesiae Persica), ed. J. Gilmore (1888), p. 38; Diodorus ii. 7.) The zodiac of the Babylonians was divided into thirty-six decans, a decan being the space the sun covered in relation to fixed stars during a ten-day period. "However, the 36 decans with their decades require a year of only 360 days." (W. Gundel, Dekane and Dekansternbilder (1936), p. 253). To explain this apparently arbitrary length of the zodiacal path, the following conjecture was made: "At first the astronomers of Babylon recognized a year of 360 days, and the division of a circle into 360 degrees must have indicated the path traversed by the sun each day in its assumed circling of the earth." (Cantor, Vorlesungen uber Gesehichie der Mathematik, I, 92.) This left over five, degrees of the zodiac unaccounted for. The old Babylonian year consisted of twelve months of thirty days each, the months being computed from the time of the appearance of the new moon. As the period between one new moon and another is about twenty-nine and a half days, students of the Babylonian calendar face the perplexity with which we are already familiar in other countries. "Months of thirty days began with the light of the new moon. How agreement with astronomical reality was effected, we do not know. The practice of an intercalary period is not yet known." ("Sin" in Roscher, Lexikon der griech. und rom. Mythologic, Col. 892.) It appears that in the seventh century five days were added to the Babylonian calendar; they were regarded as unpropitious, and people had a superstitious awe of them.

The Assyrian year consisted of 360 days; a decade was called a sarus; a sarus consisted of 3,600 days. (Georgius Syncellus, ed. Jacob Goar (Paris, 1652), pp. 17, 32.) "The Assyrians, like the Babylonians, had a year composed of lunar months, and it seems that the object of astrological reports which relate to the appearance of the moon and sun was to help to determine and foretell the length of the lunar month. If this be so, the year in common use throughout Assyria must have been lunar. The calendar assigns to each month thirty full days; the lunar month is, however, little more than twenty-nine and a half days." (R. C. Thompson, The Reports of the Magicians and Astrologers of Nineveh and Babylon in the British Museum, II (1909), xix.) "It would hardly be possible for the calendar month and the lunar month to correspond so exactly at the end of the year." (Ibid., p. xx.) Assyrian documents refer to months of thirty days only, and count such months from crescent to crescent. (Langdon and Fotheringham, The Venus Tablets of Ammizaduga, pp. 45-46; C. H. W. Johns, Assyrian Deeds and Documents, IV (1923), 333; J. Kohler and A. Ungnad, Assyrische Rechtsurkunden (1913), 258, 3; 263, 5; 649, 5.) Again, as in other countries, it is explicitly the lunar month that is computed by the Assyrian astronomers as equal to thirty days. How could the Assyrian astronomers have adjusted the length of the lunar months to the revolutions of the moon, modern scholars ask themselves, and how could the observations reported to the royal palace by the astronomers have been so consistently erroneous?

The month of the Israelites, from the fifteenth to the eighth century before the present era, was equal to thirty days, and twelve months comprised a year; there is no mention of months shorter than thirty days, nor of a year longer than twelve months. That the month was composed of thirty days is evidenced by Deuteronomy 34 : 8 and 21 : 13, and Numbers 20 : 29, where mourning for the dead is ordered for a "fall month," and is carried on for thirty days. The story of the Flood, as given in Genesis, reckons in months of thirty days; it says that one hundred and fifty days passed between the seventeenth day of the second month and the seventeenth day of the seventh month. (Genesis 7 : 11 and 24; 8:4) The Hebrews observed lunar months. This is attested to by the fact that the new-moon festivals were of great importance in the days of Judges and Kings. (1. Samuel 20 : 5-6; II Kings 4 : 23; Amos 8 : 5; Isaiah 1 : 13; Hosea 2 : 11; Ezekiel 46: 1, 3. In the Bible the month is called hodesh, or "the new (moon)," which testifies a lunation of thirty days.) "The new moon festival anciently stood at least on a level with that of the Sabbath." (J. Wellhausen. Prolegomena to the History of Israel (1885), p. 113.) As these (lunar) months were thirty days long, with no months of twenty-nine days in between, and as the year was composed of twelve such months, with no additional days or intercalated months, the Bible exegetes could find no way of reconciling three figures: 354 days, or twelve lunar months of twenty-and a half days each; 360 days, or a multiplex of twelve times thirty; and 365 1/4 days, the present length of the year.

The Egyptian year was composed of 360 days before it became 365 by the addition of five days. The calendar of the Ebers Papyrus, a document of the New Kingdom, has a year of twelve months of thirty days each. (Cf. G. Legge in Recueil de travaux relatifs a la philologie et a l' archeologie egyptiennes et assyriennes (La Mission francaise du Caire, 1909). In the ninth year of King Ptolemy Euergetes, or -238, a reform party among the Egyptian priests met at Canopus and drew up a decree; in 1866 it was discovered at Tanis in the Delta, inscribed on a tablet. The purpose of the decree was to harmonize the calendar with the seasons "according to the present arrangement of the world," as the text states. One day was ordered to be added every four years to the "three hundred and sixty days, and to the five days which were afterwards ordered to be added." (Sharpe, The Decree of Canopus (1870).) The authors of the decree did not specify the particular date which the five days were added to the 360 days, but they say clearly that such a reform was instituted on some date after the period when the year was only 360 days long. On a previous page I referred to the fact that the calendar of days was introduced in Egypt only after the close of the Middle Kingdom, in the days of the Hyksos. The five epigomena must have been added to the 360 days subsequent to the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty. We have no mention of "five days" in all the numerous inscriptions of the Eighteenth Dynasty; the epigomena or, as the Egyptians called them, "the days which are above the year," (E. Meyer, "Agyptische Chronologie, " Philos. and hist. Abhandlungen der Preuss. Akademie der Wissenschaften (1904), p. 8.) are known from the documents of the seventh and following centuries. The pharaohs of the late dynasties used to write : "The year and the five days." The last day of the year was celebrated, not on the last of the epagomena, but on the thirtieth of Mesori, the twelfth month. (E. Meyer, "Agyptische Chronologie," Philos. and hist. Abhandlungen der Preuss, Akademie der Wissenschaften (1904), p. 8.) In the fifth century Herodotus wrote: "The Egyptians, reckoning thirty days to each of the twelve months, add five days in every year over and above the number, and so the completed circle of seasons is made to agree with the calendar." (Herodotus, History, Bk. ii. 4 (transl. A. D. Godley).) The Book of Sothis, erroneously ascribed to the Egyptian priest Manetho (See volume of Manetho in Loeb Classical Library.) and Georgius Syncellus, the Byzantine chronologist (Georgii Monachi Chronographia (ed. P. Jacobi Goar, 1652), p. 123.), maintain that originally the additional five days did not follow the 360 days of the calendar, but were introduced at a later date,(In the days of the Hyksos King Aseth. But see the Section "Changes in the Times and the Seasons.") which is corroborated by the text of the Canopus Decree. That the introduction of epagomena was not the result of progress in astronomical knowledge, but was caused by an actual change in the planetary movements, is implied in the Canopus Decree, for it refers to "the amendment of the faults of the heaven." In his Isis and Osiris. (Translated by F. C. Babbit.) Plutarch describes by means of an allegory the change in the length of the year: "Hermes playing at draughts with the moon, won from her the seventieth part of each of her periods of illumination, and from all the winnings he composed five days, and intercalated them as an addition to the 360 days." Plutarch informs us also that one of these epagomena days was regarded as inauspicious; no business was transacted on that day, and even kings "would not attend to their bodies until nightfall." The new-moon festivals were very important in the days of the Eighteenth Dynasty. On all the numerous inscriptions of that period, wherever the months are mentioned, they are reckoned as thirty days long. The fact that the new-moon festivals were observed at thirty-day intervals implies that the lunar month was of that duration. Recapitulating, we find concordant data. The Canopus Decree states that at some period in the past the Egyptian year was only 360 days long, and that the five days were added at some later date; the Ebers Papyrus shows that under the Eighteeenth Dynasty the calendar had a year of 360 days divided into twelve months of thirty days each; other documents of this period also testify that the lunar month had thirty days, that a new moon was observed twelve times in a period of 360 days. The Sothis book says that this 360-day year was established under the Hyksos, who ruled after the end of the Middle Kingdom, preceding the Eighteenth Dynasty. In the eighth or seventh century the five epagomena days were added to the year under conditions which caused them to be regarded as unpropitious. Although the change in the number of days in the year was culated soon after it occurred, nevertheless, for some time many nations retained a civil year of 360 days divided into twelve months of thirty days each.

Cleobulus, who was counted among the seven sages of ancient Greece, in his famous allegory represents the year as divided into twelve months of thirty days: the father is one, the sons twelve, and each of them has thirty daughters. (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, "Life, of Thales.") From the days of Thales, another of the seven sages, who could predict an eclipse, the Hellenes knew that the year is of 365 days; Thales was regarded by them as the man who discovered the number of days in the year. As he was born the seventh century, it is not impossible that he was one of the first among the Greeks to learn the new length of the year; it was in the beginning of that century that the year achieved its present length. A contemporary of Thales and also one of the seven sages, Solon was regarded as the first among the Greeks to find that a lunar month is less than thirty days. (Proclus, The Commentaries on the Timaeus of Plato (1820); Diogenes Laertius, Lives, "Life of Solon"; Plutarch, Lives, "Life of Solon.) "Despite their knowledge of the correct measure of the year and month, the Greeks, after Solon and Thales, continued to keep to the obsolete calendar, a fact for which we have the testimony of Hippocrates ("Seven years contain 360 weeks"), Xenophon, Aristotle, and Pliny. (Aristotle, Historia animalium, vi. 20; Pliny, Natural History, xxxiv. 12 (transl. Bostock and Riley).) The persistence of reckoning 360 days is accounted for not only by a certain reverence for the earlier astronomical year, but also its convenience for computation.

The ancient Romans also reckoned 360 days to the year. Plutarch wrote in his "Life of Numa" that in the time of Romulus, in the eighth century, the Romans had a year of 360 days only. (Plutarch, Lives, "The Life of Numa," xviii.) Various Latin authors say that the ancient month was composed of thirty days. (Cf. Geminus, Elementa astronomiae, viii; cf. also Cleomedes, De motu circulari corporum celestium, xi. 4.)

On the other side of the ocean, the Mayan year consisted of 360 days; later five days were added, and the year was then a tun (360-day period) and five days; every fourth year another day was added to the year. "They did reckon them apart, and called them the days of nothing: during the which the people did not anything," wrote J. de Acosta, an early writer on America . (J. de Acosta, The Natural and Moral Histories of the Indies, 1880 (Historia natural y moral de las Indias, Seville, 1590).) Friar Diego de Landa, in his Yucatan before and after the Conquest, wrote: "They had their perfect year like ours, of 365 days and six hours, which they divided into months in two ways. In the first the months were of 30 days and were called U which signifies the moon, and they counted from the rising of the new moon until it disappeared." (Diego de Landa, Yucatan, p. 59.) The other method of reckoning, by months of twenty days' duration (uinal hunekeh), reflects a much older system, to which I shall return when I examine more archaic systems than that of the 360-day year. De Landa also wrote that the five supplementary days were regarded as "sinister and unlucky." They were called "days without name." (D. G. Brinton, The Maya Chronicles (1882).) Although the Mexicans at the time of the conquest called a thirty-day period "a moon," they knew that the synodical period is 29.5209 days, (Gates' note to De Landa, Yucatan, p. 59.) which is more exact than the Gregorian calendar introduced in Europe ninety years after the discovery of America. Obviously, they adhered to an old tradition dating from the time when the year had twelve months of thirty days each, 360 days in all. (R. C. E. Long, "ChronologyMaya," Encyclopaedia Britannica (14th ed.): They [the Mayas] never used a year of 365 days in counting the distance of time from one date to another.")

In ancient South America also the year consisted of 360 days, divided into twelve months. "The Peruvian year was divided into twelve Quilla, or moons of thirty days. Five days were added at the end, called Allcacanquis." (Markham, The Incas of Peru, p. 117.) Thereafter, a day was added every four years to keep the calendar correct.

We cross the Pacific Ocean and return to Asia. The calendar of the peoples of China had a year of 360 days divided into twelve months of thirty days each. (Joseph Scaliger, Opus de emendation temporurn, p. 225; W. Hales, New Analysis of Chronology (1809-1812), I, 31; W. D. Medhurst, notes to pp. 405-406 of his translation of The Shoo King (Shanghai, 1846).) A relic of the system of 360 days is the still persisting division the sphere into 360 degrees; each degree represented the diurnal advance of the earth on its orbit, or that position of the Zodiac which was passed over from one night to the next. After 360 changes the stellar sky returned to the same position for the observer on the earth. When the year changed from 360 to 365 1/4 days, the Chinese added five and a quarter days to their year, calling this aditional period Khe-ying; they also began to divide a sphere to 365 1/4 degrees, adopting the new year-length not only in the calendar, but also in celestial and terrestrial geometry. (H. Murray, J. Crawfurd, and others, An Historical and Descriptive Account of China (p. 235) ; The Chinese Classics, III, Pt. 2, ed. Legge (Shanghai, 1865), note to p. 21. Cf. also Cantor, Vorlesungen, p. 92. "Zuerst wurde von den Astronomen Babylons das Jahr von 360 Tagen erkannt, and die Kreisteilung in 360 Grade sollte den Weg versinnlichen welchen die Sonne bei ihrem vermeintlichen Umlaufe die Erde jeden Tag zurucklegte.") Ancient Chinese time reckoning was based on a coefficient of sixty; so also in India, Mexico, and Chaldea, sixty being the universal coefficient. The division of the year into 360 days was honoured in many ways, (C.F. Dupuis (L'Origine de tour les cultes [1835-1836], the English compendium The Origin of All Religious Worship [1872], p. 41) gathered material on the number 360, "which is that of the days of the year without the epigomena." He refers to the 360 gods in the "theology of Orpheus," to the 360 eons of the gnostic genii, to the 360 idols before the palace of Dairi in Japan, to 360 statues surrounding that of Hobal," worshipped by the ancient Arabs, to the 360 genii who take possession of the soul after death, "according to the doctrine of the Christians of St. John," to the 360 temples built on the mountain of Lowham in China, and to the wall of 360 stadia "with which Semiramis surrounded the city" of Babylon. This material did not convey to its collector the idea that an astronomical year of 360 days had been the reason for the sacredness of the number 360.) and, indeed, it became an incentive to progress in astronomy and geometry, so that people did not readily discard this method of reckoning when it became obsolete. They obtained their "moons" of thirty days, though the lunar month in fact they became shorter, and they regarded the five days as not belonging to the year.

All over the world we find that there was at some time the same calendar of 360 days, and that at some later date, about the seventh century before the present era, five days were added at the end of the year, as "days over the year," or "days of nothing." Scholars who investigated the calendars of the Incas of Peru and the Mayas of Yucatan wondered at the calendar of 360 days; so did the scholars who studied the calendars of the Egyptians, Persians, Hindus, Chaldeans, Assyrians, Hebrews, Chinese, Greeks, or Romans. Most of them, while debating the problem in their own field, did not suspect that the same problem turned up in the calendar of every nation of antiquity. Two matters appeared perplexing: a mistake of five and a quarter days in a year could certainly be traced, not only by astronomers, but even by analphabetic farmers, for in the short span of forty years a period that a person could readily observe the seasons would become displaced by more than two hundred days. The second perplexity concerns the length of a month. "It seems to have been a prevailing opinion among the ancients that a lunation or synodical month lasted thirty days." (Medhurst, The Shoo Ring.) In many documents of various peoples, it is said that the month, or the "moon," is equal to thirty days, and that the beginning of such a month coincides with the new moon. Such declarations by ancient astronomers make it clear that there was no such thing as a conventional calendar with an admitted error; as a matter of fact, the existence of an international calendar in those days is extremely unlikely. After centuries of open sea lanes and international exchange of ideas, no uniform calendar for the whole world has as yet been devised : the Moslems have a lunar year, based on the movements of the moon, which is systematically adjusted every few years to the solar year by intercalation; many other creeds and peoples have systems of their own containing many vestiges of ancient systems. The reckoning of months as equal to thirty and thirty-one days is also a relic of older systems; the five supplementary days were divided among the old lunar months. But at present the almanac does not ascribe an interval of thirty days between two lunations or a period of 360 days for twelve lunations.

The reason for the universal identity of time reckoning between the fifteenth and the eighth centuries lay in the actual movements of the earth on its axis and along its orbit, and in the revolution of the moon, during that historical period. The length of a lunar revolution must have been almost exactly 30 days, and the length of the year apparently did not vary from days by more than a few hours. Then a series of catastrophes occurred that changed the axis and the orbit of the earth and the orbit of the moon, and the ancient year, after going through a period marked by disarranged seasons, settled into a "slow-moving year" (Seneca) of 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, 46 seconds, a lunar month being equal to 29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes, 2.7 seconds, mean synodical period.